TWO GOOD TO BE TRUE

I sometimes see scripts that are pursuing multiple ideas. For example, we might have a horror script that is about two characters; one is contending with a cult, the other is contending with a slasher. It’s one thing if the cult and the slasher are connected. But if not, then we have two protagonists of two different A-stories uncomfortably residing under one title.

There is of course such a thing as sub-plotting; narratives with an A-story, a B-story, a C-story, etc. But making each of those story threads reside within its own context is an approach that better works in five-act TV writing, i.e. in this episode the A-story is about this character doing this thing (plugging into the over-arching narrative, if it’s a serialized one-hour drama), the B-story is about that character doing that thing, and so on.

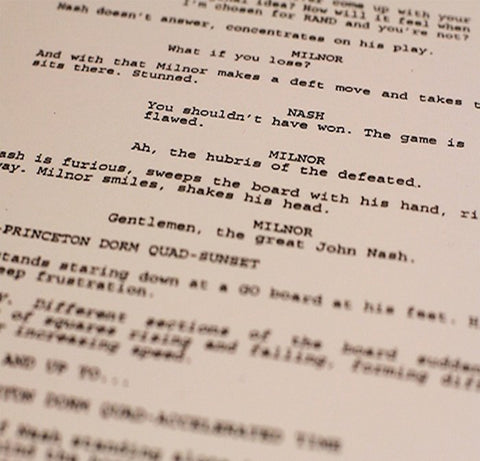

But feature film, and especially spec scripts for feature, are a much more focused storytelling medium. They play best when the story is about one protagonist who is driving a single A-story. If we have sub-plots, they function to inform the A-story. For example, we might have a B-story romance, but the love interest feeds into the A-story (as both a supporting protagonist, and a function of deepening the main protagonist’s A-story). We have one internal arc: the protagonist’s. We have one thematic statement. We have one concept.

Note that in pitching, a script has a logline. It isn’t a log-paragraph, or loglines. It’s logline, singular; usually one sentence describing one idea about one character who is driving one story told in one movie.

It’s only with this kind of narrative focus that we can shape the narrative around the structural beats of a single A-story. One dramatically powerful plot point one, that clearly delivers the function of that structural beat, is worth far more than two or three scenes that might be plot point one – maybe?

On the marketing side, let’s note that the term of the movie’s poster is “one-sheet.” It’s one poster pitching one movie to the audience, and what kind of film-going experience they can expect if they buy one ticket to see it.

Have you ever seen a one-sheet that’s too busy? We aren’t talking about the one-sheets in which we see multiple characters in an ensemble film. We’re talking about the amateur posters we see with spaceships and dinosaurs and explosions and cars and animals and a bunch of various characters. The people who mock up posters like this think they have to tell the audience about everything in the movie. The opposite is true; one single idea is worth a jumble tossed in a pile.

It is of course better to have too many ideas than too few, or none. But if we have too many ideas, instead of trying to shove them all into the same script, it’s better to parse them about across multiple scripts where each can be given the chance to breathe and develop.