THE VALUE OF DREAMS

Not long ago, I had a very long and involved dream. When I woke up, the dream and the story it told was still very vivid. I decided to put it to script. I had other projects that needed to get done, projects with deadlines. But this dream was like a rare bird that had landed on my window; I had to catch it before it flew away.

From 7am until 2pm I wrote non-stop. After 35 pages, I finally ran out of raw material from the dream. The choices I made in stitching together some of the more ephemeral elements gave me a direction; I have a firm idea as to where the rest of the story will go. Finishing the script will be just a matter of typing it.

Similarly, when I was presented with an opportunity to write and direct my first feature film, DEATH METAL, about half of the script was drawn from dreams I’d had over the years, dreams strong enough that I still carried them in memory. All the scary stuff in this horror movie comes from the delightful nightmares.

I offer these two anecdotes as examples of situations in which I have taken the stuff of dreams and put them on the page. Any movie begins with the writer’s imagination; a waking dream. And filmmaking is the act of using technology to translate the most ephemeral of things into a sharable reality. Films are sharable dreams.

Some people keep dream journals. I don’t; perhaps I should. But I still remember dreams I had many years ago, even dreams I had when I was a kid. Not all of them are as involved as the dream that gave me 35-ppg of script. I keep them in a mental file for when they might be of use.

Dreams are the most nutrient-rich source of inspiration. They are the primordial ooze that lies at the bottom of our subconscious. They are an ever-renewable resource. The mind creates them when it’s left to speak only to itself. They are of infinite value to writing.

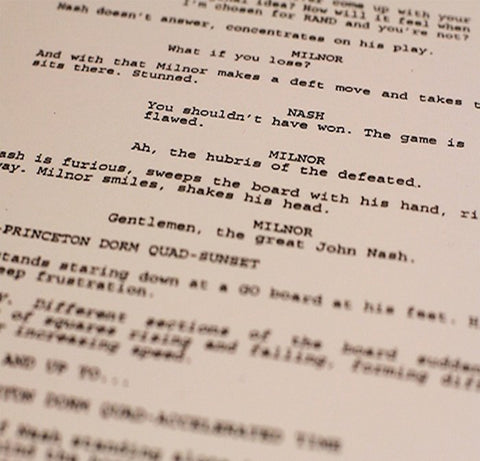

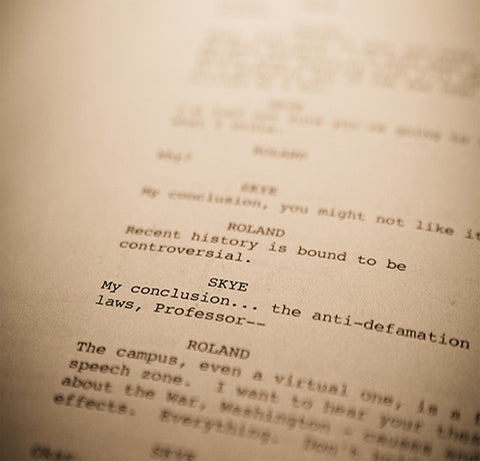

Screenwriting is a “harder” form of writing than most. It’s rigid with format rules, structural concerns, and having to eventually bring what’s on the page to the set, and thus to the screen. With screenwriting in particular, it’s very easy to be distracted by outside elements that are not the characters or their story.

Those external rigidities are just scaffolding for the dream. They exist to give form to the fire of raw imagination, so when they are taken away the dream has the solidity to stand on its own.

Everyone dreams while they nightly lie in the embrace of death’s cousin. But it’s only we, the writers, whose task it is to shape those dreams into a form that can be shared. We do so to bring a bit of happiness to our fellow humanity, a brief respite from their waking cares. And isn’t that quite wonderful?