THE PROTAGONIST IS THE STORY

The story isn’t just about the protagonist; the protagonist is the story. We should establish the protagonist as quickly as possible, and from there maintain a tight focus on the protagonist’s actions to move the story forward.

We can find examples of this in the most elemental of story forms. For example, fairy tales. “Once upon a time, there was a princess who lived in a castle…” Bang, there’s our story: a princess is living in a castle, and then something happens, so then she does X, which leads to Y, and onto Z, and so on. That’s our narrative.

Or even a joke. Jokes are stories; they are short and ultra-focused, but we still find they are built on narrative construction principles that apply to any other kind of story. For example, “A guy walks into a bar…” In this case, the joke is telling a story. Who is the story about? It’s about the guy who walks into a bar, then something happens, so the guy does X, and the bartender does Y, and so on. That’s our narrative.

The opening scene is often a statement of intention: this is our protagonist, and here is the beginning of our protagonist’s story.

For instance, let’s say we have a script that opens with a young boy who wakes up on Christmas Eve and sees Santa Claus. From that point forward, it would be weird if this story wasn’t about the boy, or Santa Claus, right?

Let’s say we open with the boy and Santa Claus, and then we shift focus to a tough detective who is chasing bank robbers… and never come back to the boy or Santa again. We’re left to wonder what was the point of the opening scene with the boy and Santa Claus. We’re left to wonder why we didn’t open on the detective and her case. As in: we’re opening the movie on a scene that feeds the audience nothing but confusion.

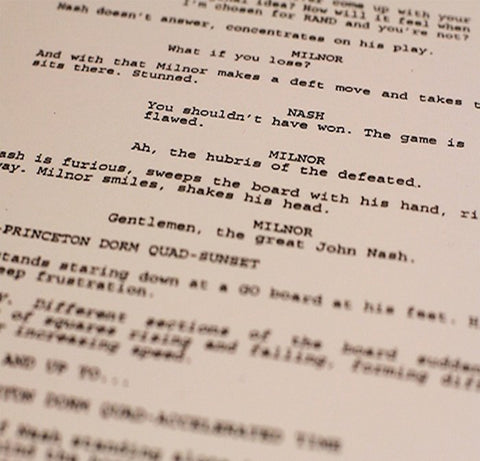

But a film like SILENCE OF THE LAMBS opens with the protagonist, Clarice Starling, being pulled from her training at the FBI Academy to interview the notorious inmate Hannibal Lecter, in an effort to gain insight on another serial killer, Buffalo Bill. These scenes set the stage for the protagonist's primary objective, her emotional flaw, and the ensuing obstacles/conflicts.

There are exceptions, of course. For example, we might also open on the antagonist. Doing so is still introducing the protagonist’s story because, by opening on the villain doing villain stuff, we’re establishing the problem that the protagonist will have to solve in the course of the story.

We often see this in horror movies: we open on a scary scene in which someone gets haunted and/or killed by the Baddie, then we cut to our protagonist who is living her normal life, knowing that she will soon encounter the Baddie, which in turn will lead to the story of her dealing with the Baddie.

We can always start from a very basic place: “This is the story of X Protagonist who wants/needs Y and does Z to get it.” From this one sentence, we have the engine that can make the narrative go. But the protagonist is the key. Without the protagonist, we have no goal or motivation; we only have incident, stuff that happens, and that by itself isn’t story.