Script Reader Pet Peeves: Simple Mistakes to Avoid In Your Script

The lowly script reader, tucked in a windowless back room at a production company or agency, holds massive power when it comes to newer writers breaking in. A poor reader’s report will sink a script from a newer writer. That lowly script reader is often the one who decides what his or her boss is going to read (or in plenty of cases, is not going to read, but will simply trust the reader’s report about).

For this reason, it is in a writer’s best interest to write a script that a reader will like. This seems obvious, but there a variety of small errors newer writers consistently make which drive script readers nuts.

Here are some script reader pet peeves, in no particular order:

PET PEEVE #1 EXPOSITIONAL DIALOGUE

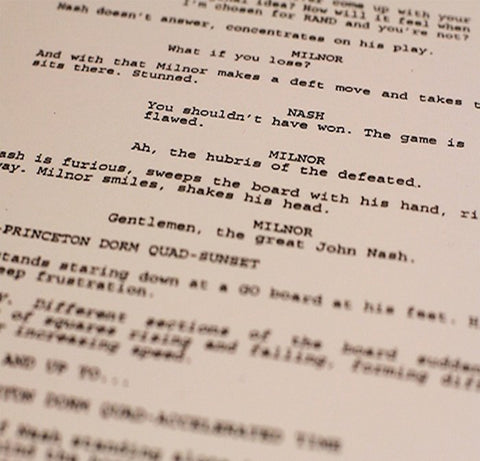

We all exist in the same world, where human beings speak to each other in the same way. This is NOT how human beings speak:

“Johnny, as you know, I’ve been a doctor for 15 years, and I remember seeing a case like this several years ago, which is why I know how to diagnose you. You shouldn’t distrust my diagnosis, I’m an expert. You have cancer.”

Here’s how this dialogue might sound in real life:

“Johnny, I’m sorry, but this isn’t a guess. You have cancer.”

It is better to err on the side of reality than strain to make the exposition of your script crystal-clear, because that can lead to expositional, unnatural dialogue.

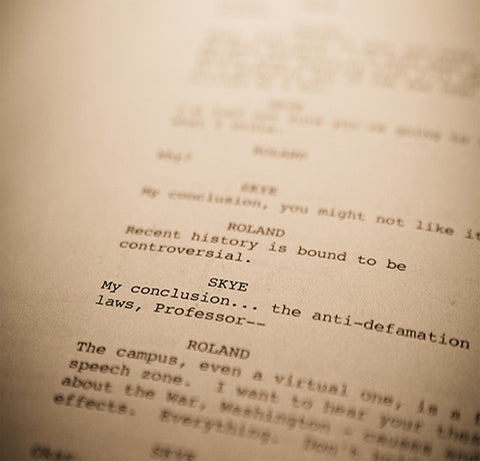

#2 THE SAME CHARACTERS

This is the introduction of the male hero in a good 25% of scripts from newer writers that come through the doors, here at ScriptArsenal:

“JOHNNY (late 20s), ruggedly handsome, doesn’t play by the rules, finishes another glass of whisky at the bar.”

The handsome rogue, who is a bit of a rebel, has a drinking problem, but is otherwise the coolest guy on planet Earth, is a recurring character in spec screenplays. For reasons unknown, this character is also often in their late 20s. This does not make the character more casting-friendly, the amount of bankable movie stars in their late 20s (versus, say, late 30s-50s) is low. Everyone in a movie is going to be handsome or beautiful unless otherwise specified. A character who “doesn’t play by the rules” or any variation of that is a cliché as the protagonist, as is having a drinking problem. Any one of these factors could be fine in an otherwise unique character, but the combination is one of the most consistent clichés we see in spec scripts.

#3 FLAT WRITING ON THE PAGE

Just because a script is a blueprint for a film doesn’t mean it should read like one. These should not be dry, dull technical documents. Here’s an example:

“JOHNNY, average guy, walks into his house. It’s a typical small suburban house in a rural town.”

Here’s a non-flat version of the same description:

“JOHNNY, crushingly normal, meanders into his home. Like Johnny, the house he lives in is painfully standard, the type of place that’s practically invisible even if you’re looking right at it.”

The latter has the exact same content, but that content is delivered with some authorial voice, and carefully chosen verbiage to color the scene.

#4 PROGRAMMER PLOTS, TENTPOLE BUDGETS

If the premise of your script is not wildly high concept, your budget should not be wildly high. Here’s a programmer premise:

“Two cops try to track down a serial killer.”

That is low-concept. Therefore, the budget should also be low.

“A cop and a terrorist switch faces, so the cop (taking on the terrorist’s appearance) can go undercover and stop a bombing.”

That’s high-concept. Therefore, the budget can potentially be high. That’s also the concept for FACE-OFF, the John Travolta/Nicolas Cage/John Woo film.

#5 LONG SCRIPTS

In 2019, the length of the average spec script has declined from what it was 10 or 15 years ago. 120+ pages is not a prerequisite for writing a script. Especially as a newer writer, you do not need to write a 127-page romantic comedy.

Most spec scripts now clock in somewhere between 100-110 pages. By contemporary spec standards, 120 pages is slightly on the long side, and north of 120 pages is especially long. There is no despair for a reader quite like cracking open a 133-page spec script from a newer writer.

Avoid these reader pet peeves, and give yourself the best chance of success with your spec script.