ON DIALOGUE

Dialogue is one of the trickier aspects of writing because, unlike elements like structure or format, there are no hard-and-fast rules to act as a guide. But we still know dialogue is good or bad when we hear it.

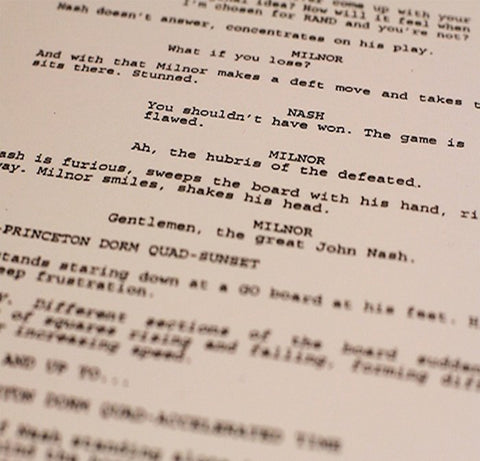

Dialogue is one of the main lures for attracting name talent (i.e. movie stars) to a project. Given that financing is often contingent on name attachments, the level of dialogue can have a direct impact on a script getting traction toward production.

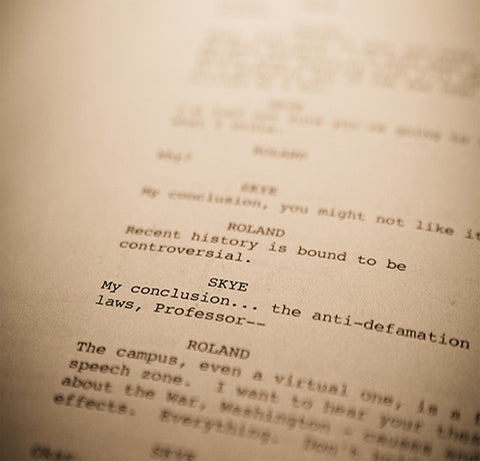

One of the main things we want to achieve is to strike a balance between clarity and character. In terms of clarity: simply put, the audience should understand what the character is saying and why. The intent of the line is clear.

However, there is such a thing as “too much” clarity, which often comes when characters bluntly state exactly what they are thinking and feeling and why, and do so in wooden terms. “I am angry at you.” “I am very sad right now.”

This kind of leaden, obvious dialogue is often called “on-the-nose.” It’s a very common reason for a script to draw a pass. “I couldn’t get into the read; the dialogue was super on-the-nose. Pass.” On-the-nose dialogue may also be caused by the delivery of blunt exposition. “Ever since I graduated from medical school at the top of my class in 2003, I have devoted my life to healing the sick because my mom died of cancer when I was a child and that made me sad.”

On-the-nose dialogue doesn’t work because it reminds us this isn’t a human being speaking; this is a golem in a screenplay. On-the-nose dialogue can be combatted by finding organic ways into the thought, typically in a manner that is unique to the character.

However, we can also err too far in that direction. While we don’t want to be so super-clear that we lose the music of the language, we still need clarity. I have read a lot of scripts in which the characters are so obtuse or arcane that it’s hard to tell what they’re saying or why. “Four points double-flippin’ banjo, heads up, Sherlock! Where’s the sun rising?”

Uh-huh.

This kind of gonzo dialogue often occurs because the writer knows what the character is saying and why, but hasn’t built a way into the thought for the audience. Even if characters use slang or jargon, we should be able to tease out the meaning through the context. For example, HEATHERS lades its characters with made-up teen-speak, but we can still parse the meaning of lines like, “What’s your damage?!”

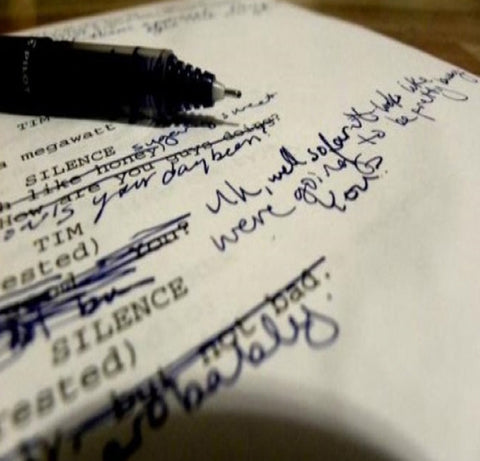

The best way to check your dialogue is to run the lines and try to sell them as the cast will need to do on set. Running lines with someone else is best, especially if that other person happens to be an actor. But even if you’re just running the lines by yourself, listen carefully: Do you hear clunks and thuds? Or music?