ON CINEMATIC STORYTELLING

I read a lot of scripts that read more like a novel’s worth of story shoved into a script-sized container. We get a sprawling ensemble of dozens of named characters, tons of plot threads, massive amounts of dialogue, and so on.

It’s one thing if the script actually is an adaptation of a novel. But note that, even in that situation, the key word is adaptation. Not only is the story rendered in screenplay format, but very often adapting the novel to the script means finding the “movie version” of the narrative. Doing so usually means losing and/or combining characters, dropping out sub-plots, and simplifying the A-story. The script is adapting the novel, not just re-telling it.

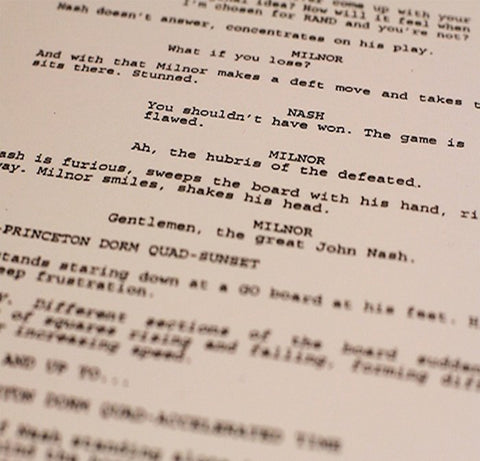

Now look at the spec script that reads like an adaptation of a novel that doesn’t exist; it has all of the burdens, but none of the focus that would give us the “movie version” of the story. But that’s antithetical to the form. A script is the blueprint for a movie. A script is telling a story, though by its very nature it should be, needs to be telling the movie version. Otherwise, we have to ask: Why is this a script, at all? Why isn’t this story being told in a novel? Or if we want to remain within the visual realm – a pilot and/or mini-series?

The movie version is the version that can be well-told within the standard runtime of a feature film, about 90-120 minutes or so. Within that frame, it’s better to find one core idea that can then be thoroughly explored, and one core character who can be thoroughly developed. We can tell a story in a movie with one character, built around one narrative idea.

That is the most basic need. Anything less, and we’re looking at a weird, static, experimental arthouse film; it’s technically “cinema” if it’s shot with a camera and projected for an audience. But it isn’t cinematic storytelling, i.e. the main thing we’re selling when someone buys a movie ticket for almost any film that requires a screenplay.

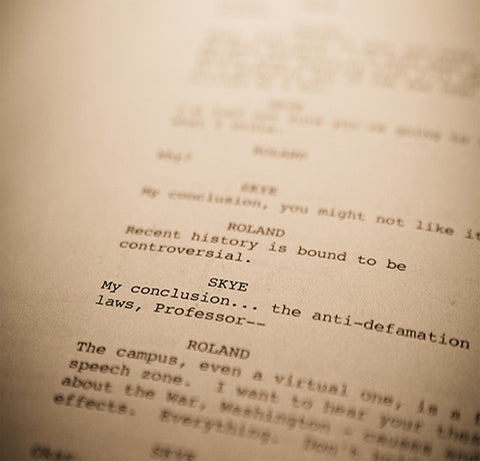

However, anything more than a single character and single narrative idea has to demand its inclusion; it must be absolutely necessary. Anything that is necessary to the story is story. Anything that is not necessary to the story is not story, so we have to ask why it’s in the “story.”

And to tell the movie version, we need to find the reason why this story is being told via the cinematic medium. Cinema’s strength lies with the moving image. Thus, a story that is told via cinema should draw most from the moving image. That is: a story that involves movement, action, motion. A story that is not primarily motivated by the moving image is not drawing on the cinematic medium.

If you have a story that would be better served by a novel, write the novel. Write the script only if the story is best told as a movie.